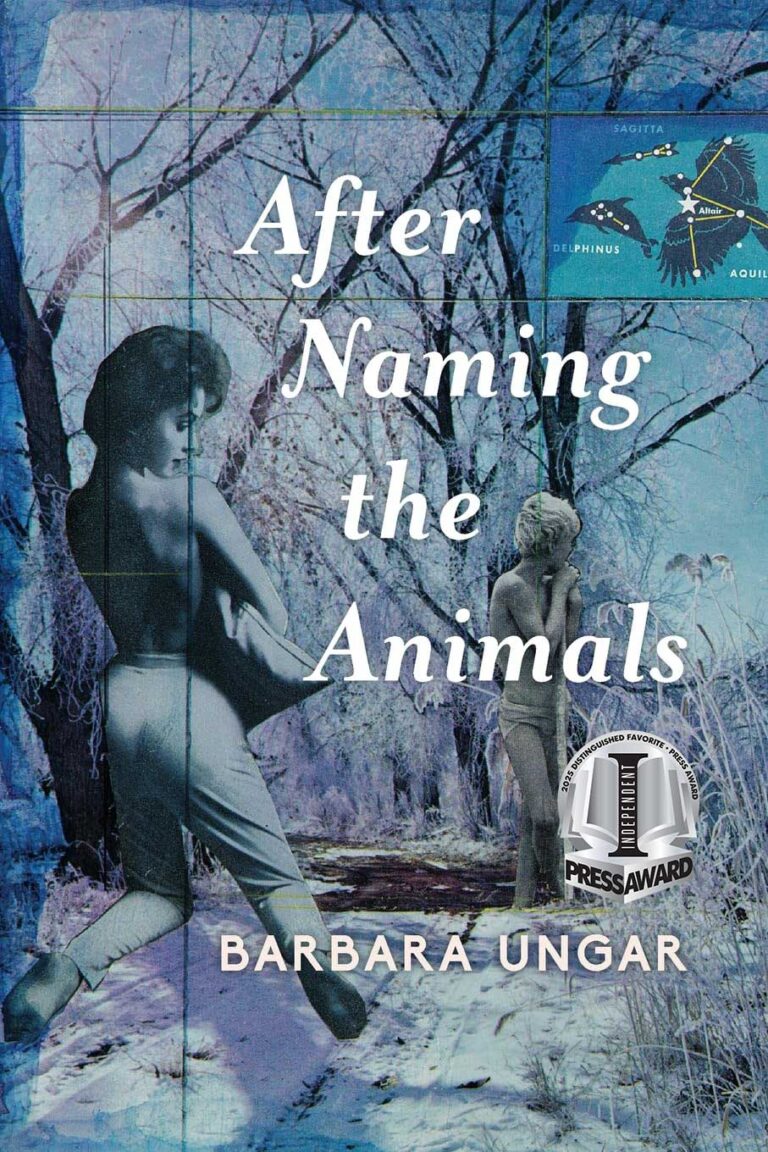

After Naming the Animals

Distinguished Favorite” by the “Independent Press Awards”

“Barbara Ungar’s latest collection, fiercer and funnier than ever, defends the planet and gives us the heart to join her in the fight. Celebration of our most startling animal cohabitants matches her insight into the human foibles that have brought us so near the brink of extinction, all with such originality that we can only feel the joy of creation and a determination to protect what matters most: this extraordinary world, and each other.”

Order from

Praise

After Naming the Animals exquisitely reveals the scale and magnitude of our collective knack for soiling our own nest. In a book by turns energizing, infuriating, mind-blowing, and devastating, Ungar’s superpower is her gift for language: “We’ve made a billion elephants’ worth of plastic,” and “Weep into your soup; under a third of birds / fly free — the rest, poultry” she quips. I found her insistent reminders that humans make up “a hundredth of a hundredth / of the living, .01%” and that atoms are “9,999 parts / empty space” weirdly reassuring. An eco-poetics virtuoso, Ungar’s infectious enthusiasm for ferruginous pygmy owls, tiny tarantulas, minute leaf chameleons, bumble bee bats, jaguars, and blue dragons with “six appendages / like six tiny headdresses for Cher” kept me agog and rapt. While inviting us to consider our perilous state, Ungar’s wide-eyed wonder and against-all-odds hope are, thankfully, contagious. —Martha Silano, author of Gravity Assist

“A poetic chiaroscuro of grief over a planet and society in peril.” —Kirkus Reviews

“This is easily the best book yet from a poet already known for her unique blend of precise lyrical craft and somersaulting wit, brimming end-to-end with observations that slice through our complacency like a scalpel made of obsidian. But there’s also a wild kindness to these poems, a fierceness born from heartbreak and the realization that, yes, the same soil that gives us flowers is also filled with bones, hard and brittle in the dark.” —Michael Meyerhofer, Ragged Eden

“We have paved the Earth with chicken bones,” Barbara Ungar mourns in her breathtaking new collection, After Naming the Animals. In a masterfully braided web of dread, humor, tenderness, brutal honesty, and exquisite lyricism, Ungar scrutinizes our human-made-apocalyptic world. After Naming the Animals provides the nourishment of becoming “your own neighborhood myth” while reconfiguring a relationship with the garden, a reckoning with our biblical, familial, and historical pasts. To name is also to plant a seed in “fertile ground in which to grow./ On the very last day, amidst the flames.” —Carlie Hoffman, When There Was Light, winner of the National Jewish Book Award

POEMS

“Weight”

Scientific American

“Chava, the Mother of All the Living”

Small Orange Journal

“Dream Voice”

The Pedestal Magazine

“How to Age Gracefully”

The Pedestal Magazine

“In Which I Fear the Coronavirus is All My Fault”

Gargoyle

“Kabbalah Barbie”

Atticus Review

“Kintsugi for Aunt Vera”

Hypertext

“On Teaching. Homer for Thirty Years”

Hypertext

“Santa Barbara”

Psaltery and Lyre

“Self-Diagnosis”

“Peri-Apocalypse Now”

“Cruising for Seniors”

“22 Extinctions in 2021”

Gargoyle

“Thought Cloud”

Atticus Review

“Ukiyo-e”

Hypertext

INTERVIEW

Local Poet Barbara Ungar talks “after naming the animals”

REVIEWS

“Humans comprise a mere hundredth/ of a hundredth of the living, .01%,” Ungar writes in “Weight.” Later, in “Average Monkey,” she informs us “We’ve made a billion elephants’/ worth of plastic.” In this significant — and gorgeous — contribution to the field of ecopoetics, Ungar toggles between the macro and the micro, erasing the distance between the two. I never thought I’d love a poem about a slug, but here we are. “My Head and I” takes us from the sea slug (elysia marginata) to Ann Boleyn to a science lesson (“A gland in the slug’s head stores/ chloroplasts from algae to keep it alive/ by photosynthesis, while a new body/ grows like a leaf from the cut neck./ The new heart starts beating in a week.”) to the speaker’s dream of hanging her own head “like a purse” on the hook of a bathroom stall. It’s a poem about identity that echoes back to the book’s opening poem which asks “What are you?” That’s the ultimate question, isn’t it? What are we, we who have squandered everything we’ve been bestowed? There are so many lines in this book that could be on bumper stickers or billboards, not because they’re cheesy but because they’re so concisely profound. (Examples: From “As If,”: “Daylight doesn’t need saving./ We need daylight to save/ us.” From “Peri-Apocalypse Now”: “Fuck reality, back to the movie.” From “Luck”: “Where on earth is not ploughed/ with someone else’s bones?”) In “Kintsugi for Aunt Vera,” a beloved teacup is shattered thanks to a caroming cat (something I can relate to as servant to 3 Siamese). The speaker contemplates sending it to Japan (the cup, not the cat) or finding someone closer who “knows how to mend precious pottery with gold/ to make it even more exquisite.” If only the art of Kintsugi could save our broken planet. —Erin C. Murphy